Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

Download the Skill

The Tautai Principle: A 12-Part Series on Strategic Adaptivity Part 7 of 12

The Difference Between Success and Survival

Most organizations manage for performance. Few manage for viability.

The difference matters more than we like to admit.

Two Different Questions

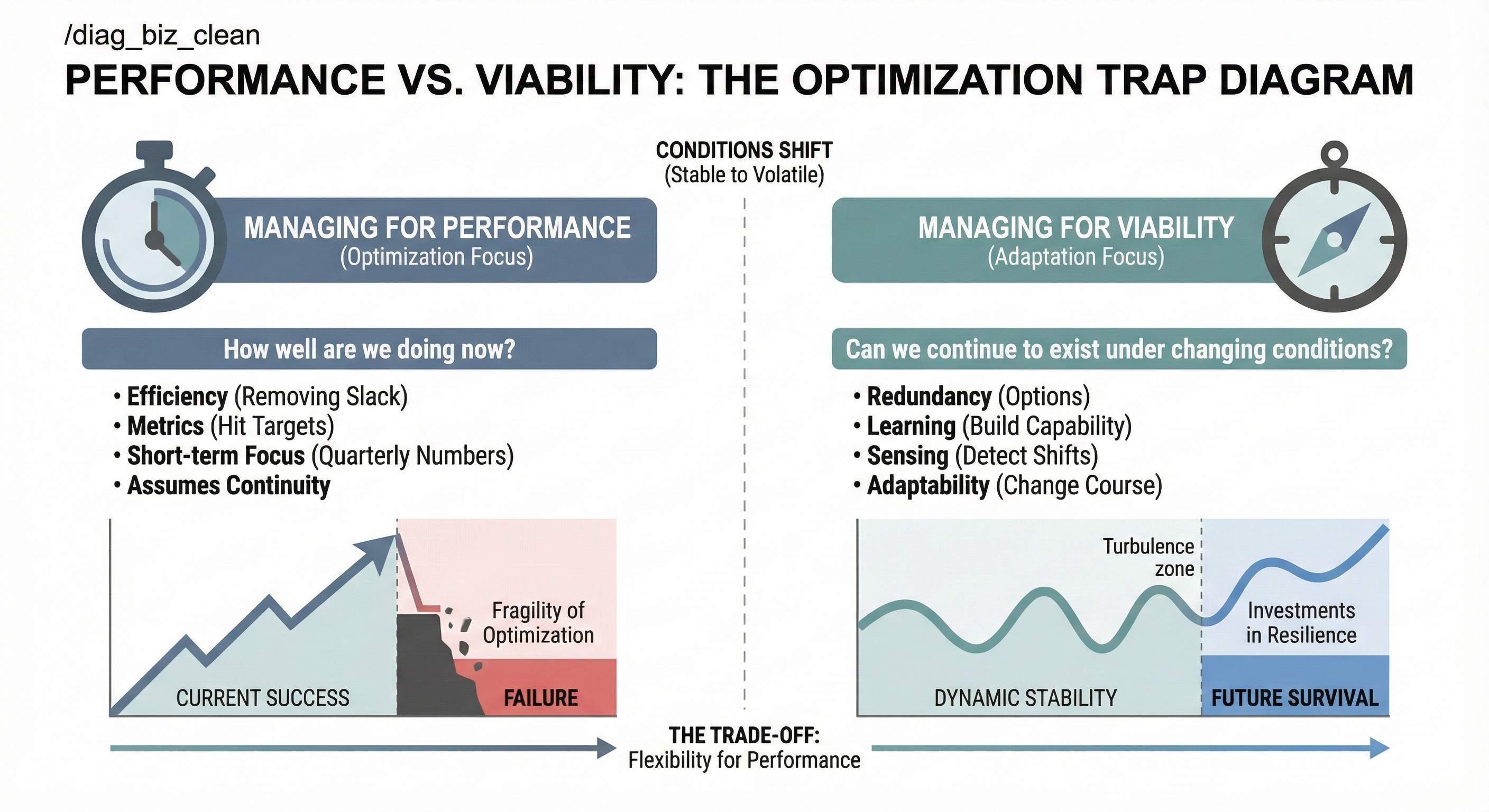

Performance asks: "How well are we doing now?"

Viability asks: "Can we continue to exist under changing conditions?"

In stable environments, performance metrics are enough. You optimize, you measure, you improve. The past predicts the future well enough that current success indicates future health.

In volatile environments, performance metrics can be dangerously misleading. An organization can hit every target, exceed every benchmark, and still be losing the capacity to adapt. By the time the numbers reflect the problem, the window for response has narrowed.

The Fragility of Optimization

In Part 6, I described the Speed Gap—the delay between reality changing and the organization responding. Highly optimized systems widen that gap. They remove slack. They narrow options. They assume continuity.

Optimization is not neutral. Every efficiency gain trades flexibility for performance. That trade works when conditions hold. When they shift, the organization lacks the capacity to respond.

This is why viability is not about maximizing performance. It's about maintaining what I call Dynamic Stability—the capacity to stay coherent while continuously adapting. Not rigid stability that resists change. Not chaotic flexibility that loses identity. Something in between: coherence through change.

What Viable Organizations Invest In

Viable organizations invest in things that look inefficient on a spreadsheet: redundancy that provides options when primary approaches fail, learning that builds capability before it's urgently needed, sensing that detects shifts before they become crises, adaptability that preserves the capacity to change course.

These investments don't optimize current performance. They protect future viability. The distinction matters because what keeps you alive under stress often looks unnecessary when stress is absent.

In Parts 4 and 5, I described sensemaking and weak signal detection. These are viability investments. They don't improve quarterly numbers. They improve the organization's capacity to notice and respond when conditions shift.

The Optimization Trap

The trap is mistaking efficiency for health. Cutting slack feels responsible. Eliminating redundancy looks like good management. Tightening processes demonstrates rigor.

Until conditions shift—and the organization discovers it has optimized away its capacity to adapt.

Viability requires asking uncomfortable questions: What are we preserving that we might need later? What sensing capability are we maintaining even without immediate payoff? What flexibility are we protecting from the pressure to optimize?

A Closing Question

Performance is a strategy. Viability is a condition.

Where are you optimizing performance at the expense of future survival?

This is Part 7 of a 12-part series introducing the ideas from my book, The Tautai Principle: Growing the Adaptive Organization (2025).

Next week in Part 8: Why some organizations survive everything—and others don't. The minimum conditions for viability that org charts miss.

Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

Speed is not about working faster—it's about responding in time. The Speed Gap between signal detection and meaningful action determines whether adaptation succeeds.

Organizations Have an Anatomy We Rarely See

Some organizations absorb shocks and adapt, others collapse under mild stress. The difference is structure—vital functions that org charts hide but viability requires.

- How to work with Skills

- Your organization doesn’t need a better plan

- Most Failures Start Before the First Decision Is Made

- When Good Management Becomes the Problem

- Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

- Crises Are Rarely Sudden

- Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

- Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

- Organizations Have an Anatomy We Rarely See

- Leadership Overload Is a Design Failure

- Innovation Fails Because of Structure, Not Ideas

- AI Won't Make Your Organization Smarter

- Adaptivity Is Not a Belief