Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

Download the Skill

The Tautai Principle: A 12-Part Series on Strategic Adaptivity Part 6 of 12

Why the Speed Gap Determines Whether Adaptation Succeeds or Fails

Many organizations pride themselves on speed. Fast teams. Fast execution. Fast delivery.

And still, they respond too late.

Speed Is Not About Working Faster

Speed is about responding in time.

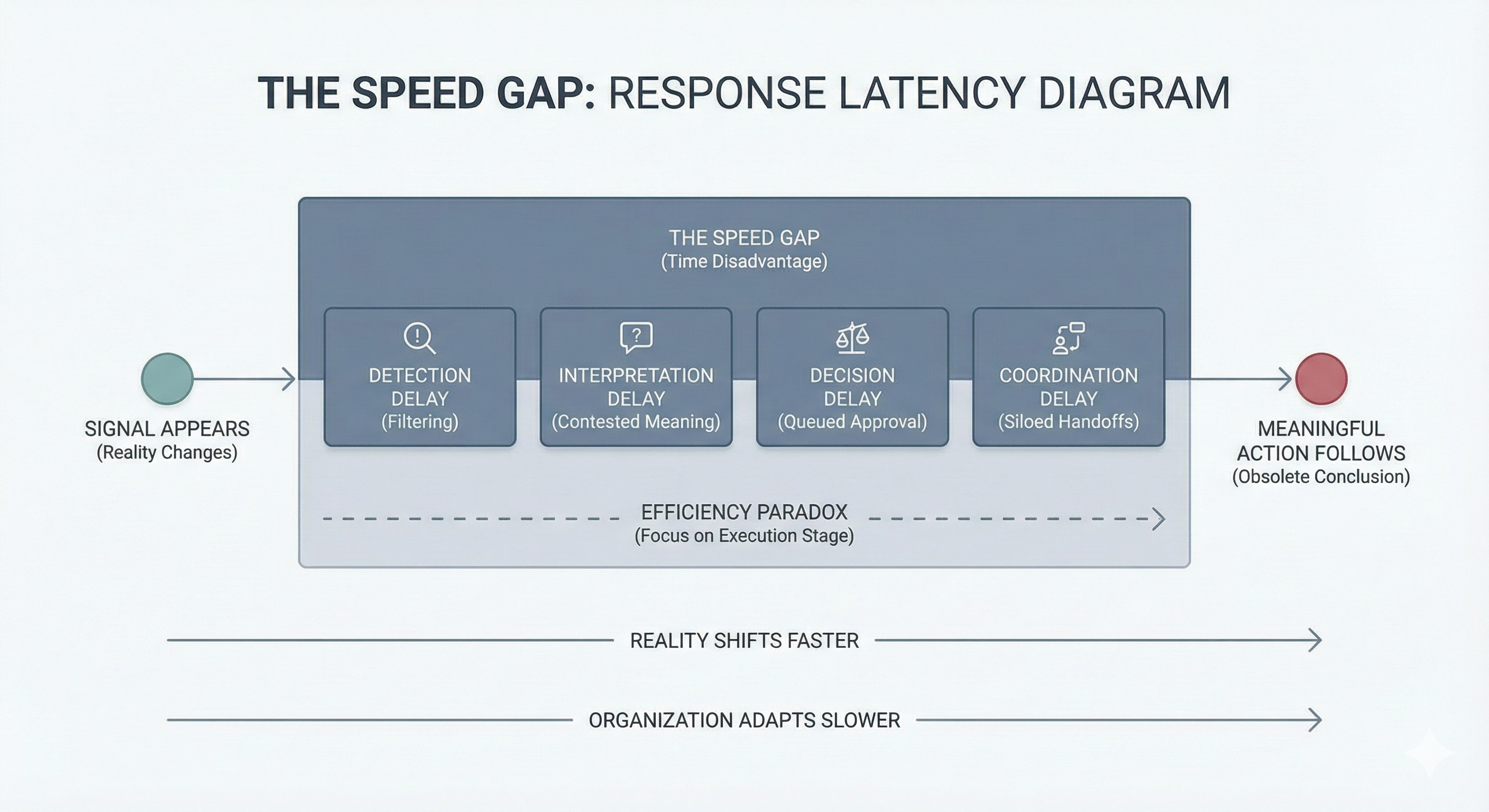

There is always a gap between how fast reality changes and how fast the organization adapts. I call this the Speed Gap—the time disadvantage between when a signal appears and when meaningful action follows. When that gap widens, viability erodes. Not suddenly, but steadily.

In Part 5, I described weak signals—the early indicators that organizations tend to filter out. The Speed Gap is what happens next. Even when signals are detected, they must travel through interpretation, decision-making, and coordination before action occurs. Every stage introduces delay.

The Efficiency Paradox

Most attempts to close this gap focus on efficiency: streamlining processes, tightening governance, optimizing workflows.

Paradoxically, this often makes organizations slower.

Efficiency improvements typically target execution—the final stage. But the largest delays rarely sit there. They sit earlier: in the time it takes to notice something, to interpret it correctly, to make a decision, to coordinate a response. Tighter governance can actually increase these delays by adding approval layers that queue decisions.

Speed is not an individual issue. It's a system property. You cannot make an organization faster by making individuals work harder.

Decision Latency Matters More Than Execution Speed

The critical measure is Response Time—the speed from signal detection to meaningful action. If it takes weeks to notice, interpret, and decide, perfect execution won't save you. You'll execute well on conclusions that are already obsolete.

This connects to Part 4's sensemaking loop. When perception is slow, meaning is contested, and decisions queue for escalation, the Speed Gap compounds. By the time action happens, the situation has already shifted.

The Structural Question

The trap is blaming people for slowness. Leaders push harder. Teams work longer. Nothing fundamentally changes.

The real question is structural. Where does information get stuck? Where do decisions queue? Where does escalation replace judgment? Where do people wait for permission that could be designed out of the system?

These are not personal failures. They are design choices—often made for good reasons that no longer apply.

A Closing Question

If reality moves faster than your decisions, it doesn't matter how well you execute.

Where is your organization fast—and still too slow?

This is Part 6 of a 12-part series introducing the ideas from my book, The Tautai Principle: Growing the Adaptive Organization (2025).

Next week in Part 7: Why your KPIs might look great while your organization isn't—and the difference between performance and viability.

Crises Are Rarely Sudden

Most crises feel unexpected, but the signals were always there—weak, ambiguous, and inconvenient. Organizations systematically filter out early warnings.

Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

Most organizations manage for performance, few for viability. An organization can hit every target while losing the capacity to adapt—and by then, the window for response has narrowed.

- How to work with Skills

- Your organization doesn’t need a better plan

- Most Failures Start Before the First Decision Is Made

- When Good Management Becomes the Problem

- Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

- Crises Are Rarely Sudden

- Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

- Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

- Organizations Have an Anatomy We Rarely See

- Leadership Overload Is a Design Failure

- Innovation Fails Because of Structure, Not Ideas

- AI Won't Make Your Organization Smarter

- Adaptivity Is Not a Belief