Crises Are Rarely Sudden

Download the Skill

The Tautai Principle: A 12-Part Series on Strategic Adaptivity Part 5 of 12

The Signals Were Always There—We Just Didn't See Them

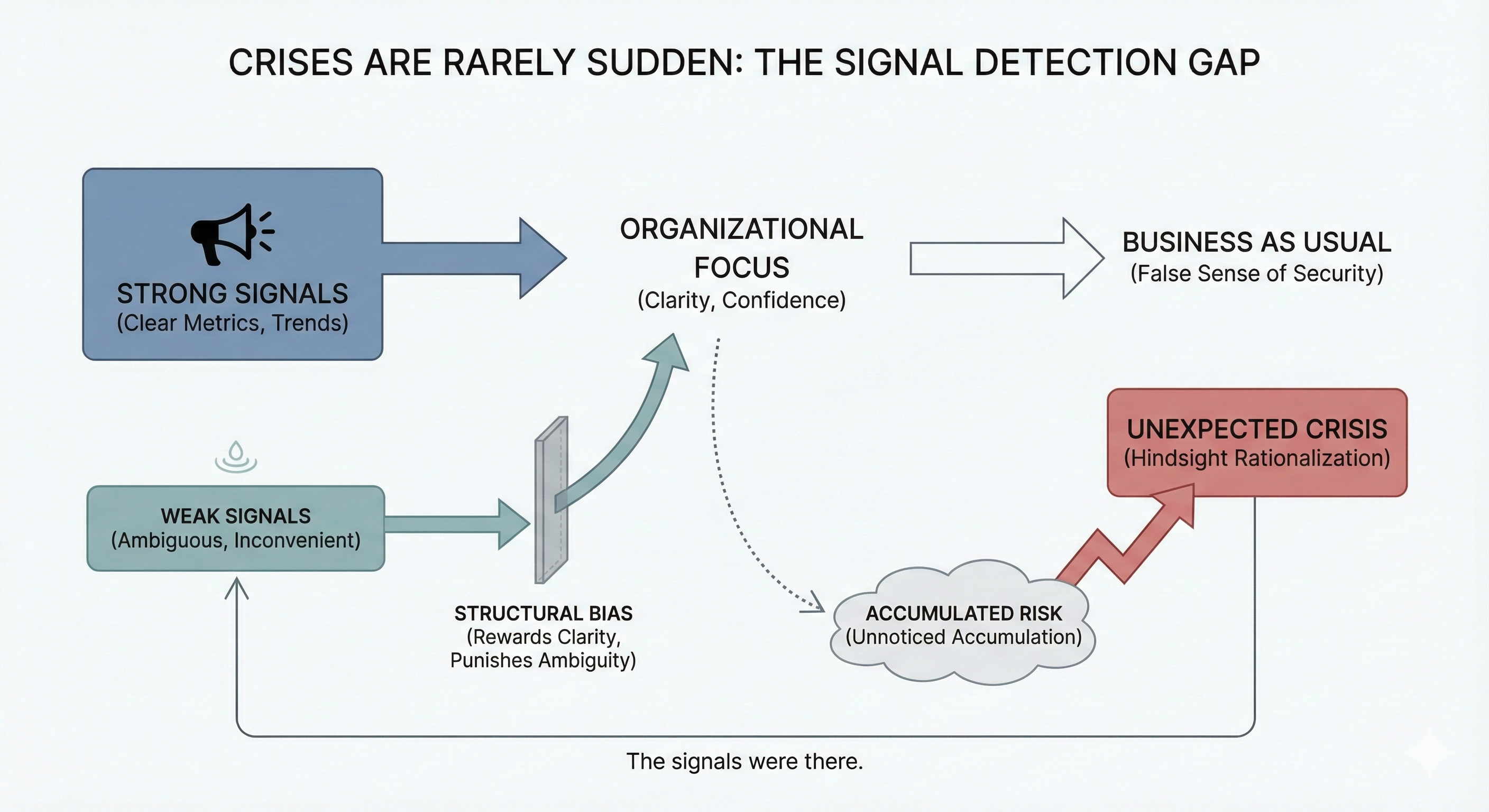

Most crises feel unexpected. In hindsight, they rarely are.

The signals were there. They were just weak, ambiguous, and inconvenient.

What Weak Signals Look Like

Weak signals don't announce themselves. They look like odd customer behavior that doesn't fit the pattern. Isolated incidents that could be noise. Uneasy intuitions from people close to the work. A comment in a meeting that gets passed over. A data point that contradicts the prevailing narrative.

Which is exactly why they are ignored.

In Part 4, I described the sensemaking loop: perception → meaning → action. Weak signals are where that loop is most vulnerable. They sit at the edge of perception, easy to filter out before they ever reach interpretation.

The Structural Bias Against Ambiguity

Organizations are very good at amplifying strong signals—clear metrics, clear trends, clear narratives. They are equally good at suppressing weak ones.

Not because leaders are blind. But because structures reward clarity and punish ambiguity. Meetings have agendas. Reports need conclusions. Decisions require confidence. In that environment, raising something vague, uncertain, or merely uncomfortable feels like a risk.

The result is predictable: what feels "too early" to raise becomes what hurts most later.

Detection Is Not a Tooling Problem

The reflex is to solve this with better dashboards or more data. But weak signal detection is not a tooling problem. It's a cultural and structural one.

The question is not whether information exists. It's whether the organization creates conditions where ambiguous, uncomfortable, or inconvenient observations can surface and be taken seriously. This is central to what I call Distributed Intelligence—building sensing capability across the organization rather than relying on filtered information reaching the top.

When frontline employees notice something strange but don't feel safe or legitimate enough to raise it, the organization loses its peripheral vision.

The Hindsight Trap

The common trap is hindsight rationalization: "No one could have known."

Usually, someone did. They just didn't feel authorized to say it. Or they said it and were dismissed. Or the signal was buried in noise that the system wasn't designed to sort through.

Weak signals require a different kind of attention—not the attention that confirms what we already believe, but the attention that notices what doesn't fit.

A Closing Question

What you don't allow to be said early will force itself on you later.

Which signals feel uncomfortable to talk about right now?

This is Part 5 of a 12-part series introducing the ideas from my book, The Tautai Principle: Growing the Adaptive Organization (2025).

Next week in Part 6: How fast is your organization—compared to reality? Why the speed gap determines whether adaptation succeeds or fails.

Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

Most organizations don't lack information—they lack shared meaning. When the sensemaking loop breaks down, no amount of strategic planning compensates.

Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

Speed is not about working faster—it's about responding in time. The Speed Gap between signal detection and meaningful action determines whether adaptation succeeds.

- How to work with Skills

- Your organization doesn’t need a better plan

- Most Failures Start Before the First Decision Is Made

- When Good Management Becomes the Problem

- Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

- Crises Are Rarely Sudden

- Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

- Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

- Organizations Have an Anatomy We Rarely See

- Leadership Overload Is a Design Failure

- Innovation Fails Because of Structure, Not Ideas

- AI Won't Make Your Organization Smarter

- Adaptivity Is Not a Belief