Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

Download the Skill

The Tautai Principle: A 12-Part Series on Strategic Adaptivity Part 4 of 12

Why Your Strategy Problem Might Actually Be a Perception Problem

Most organizations don't lack information. They lack shared meaning.

You can see it when teams interpret the same data differently, when alignment meetings multiply without alignment emerging, when decisions stall because "we don't see it the same way."

This is not a strategy problem. It's a sensemaking problem.

The Loop That Holds Everything Together

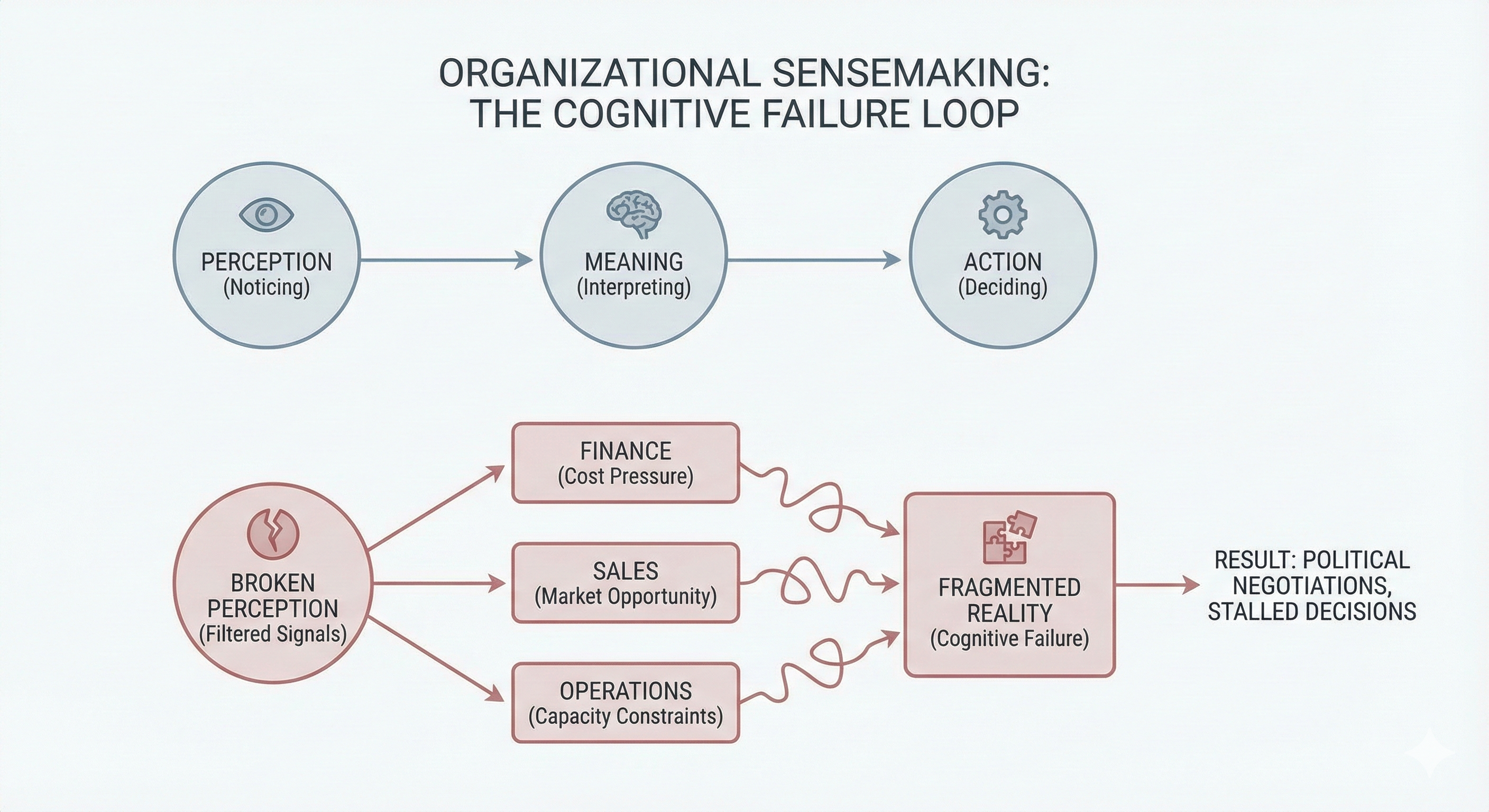

Sensemaking is the process by which organizations notice what is happening, interpret what it means, and decide how to act. It's a simple loop: perception → meaning → action.

When that loop works, organizations respond coherently to changing conditions. When it degrades, reality becomes fragmented—and no amount of strategic planning compensates.

In Part 1, I introduced the Tautai Principle: navigation over planning, sensing over prediction. Sensemaking is how that sensing actually happens. It's the cognitive infrastructure that determines whether an organization can orient itself or not.

What Breaks First

What usually breaks first is perception. Uncomfortable signals are filtered out. Ambiguous information is dismissed. Only what fits existing narratives survives.

Then meaning diverges. Different parts of the organization tell different stories about the same situation. Finance sees cost pressure. Sales sees market opportunity. Operations sees capacity constraints. Each perspective is valid—but without shared interpretation, they pull in different directions.

Action follows confusion. Decisions become political negotiations rather than responses to reality.

Alignment Starts Earlier Than You Think

The trap is believing that alignment starts with goals. It doesn't. Alignment starts with shared interpretation—a common understanding of what is happening and what it means.

Without that foundation, execution excellence only accelerates misdirection. You optimize toward a reality that no longer exists, or that only part of the organization perceives.

In Part 3, I described management traps—practices that outlive their context. A broken sensemaking loop is often what keeps those traps invisible. When perception is filtered and meaning is fragmented, outdated assumptions go unchallenged.

Why Communication Doesn't Fix This

The reflex is to fix sensemaking problems with communication. More slides. More town halls. More messaging.

But more communication doesn't restore perception. It doesn't create meaning. What's needed is something different: space to notice, question, and interpret together. Not alignment through messaging, but alignment through shared inquiry.

This is one dimension of what I call Distributed Intelligence—building sensing capability across the organization rather than concentrating it at the top. When sensemaking is distributed, the loop stays intact even as conditions shift.

A Closing Question

Organizations fail cognitively long before numbers confirm it. Where is reality filtered before it is discussed in your organization?

This is Part 4 of a 12-part series introducing the ideas from my book, The Tautai Principle: Growing the Adaptive Organization (2025).

Next week in Part 5: Why crises are rarely sudden—they are ignored. And why the signals were always there.

When Good Management Becomes the Problem

Management practices fail not because they are wrong, but because they outlive the conditions that made them successful. Competence can accelerate failure when context shifts.

Crises Are Rarely Sudden

Most crises feel unexpected, but the signals were always there—weak, ambiguous, and inconvenient. Organizations systematically filter out early warnings.

- How to work with Skills

- Your organization doesn’t need a better plan

- Most Failures Start Before the First Decision Is Made

- When Good Management Becomes the Problem

- Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

- Crises Are Rarely Sudden

- Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

- Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

- Organizations Have an Anatomy We Rarely See

- Leadership Overload Is a Design Failure

- Innovation Fails Because of Structure, Not Ideas

- AI Won't Make Your Organization Smarter

- Adaptivity Is Not a Belief