Most Failures Start Before the First Decision Is Made

Download the Skill

The Tautai Principle: A 12-Part Series on Strategic Adaptivity Part 2 of 12

The Distinction That Determines Whether Planning Helps or Harms

Most organizations don't fail because they choose the wrong strategy. They fail because they start from the wrong assumption about the situation.

You can see it in the symptoms: exhaustive analyses that still lead to surprise, plans that feel rigorous and still don't hold, confidence early on followed by confusion later.

When this happens, leaders usually ask: "What should we do differently?"

That question already assumes too much.

The Question Before the Question

The more fundamental question is: "What kind of situation are we in?"

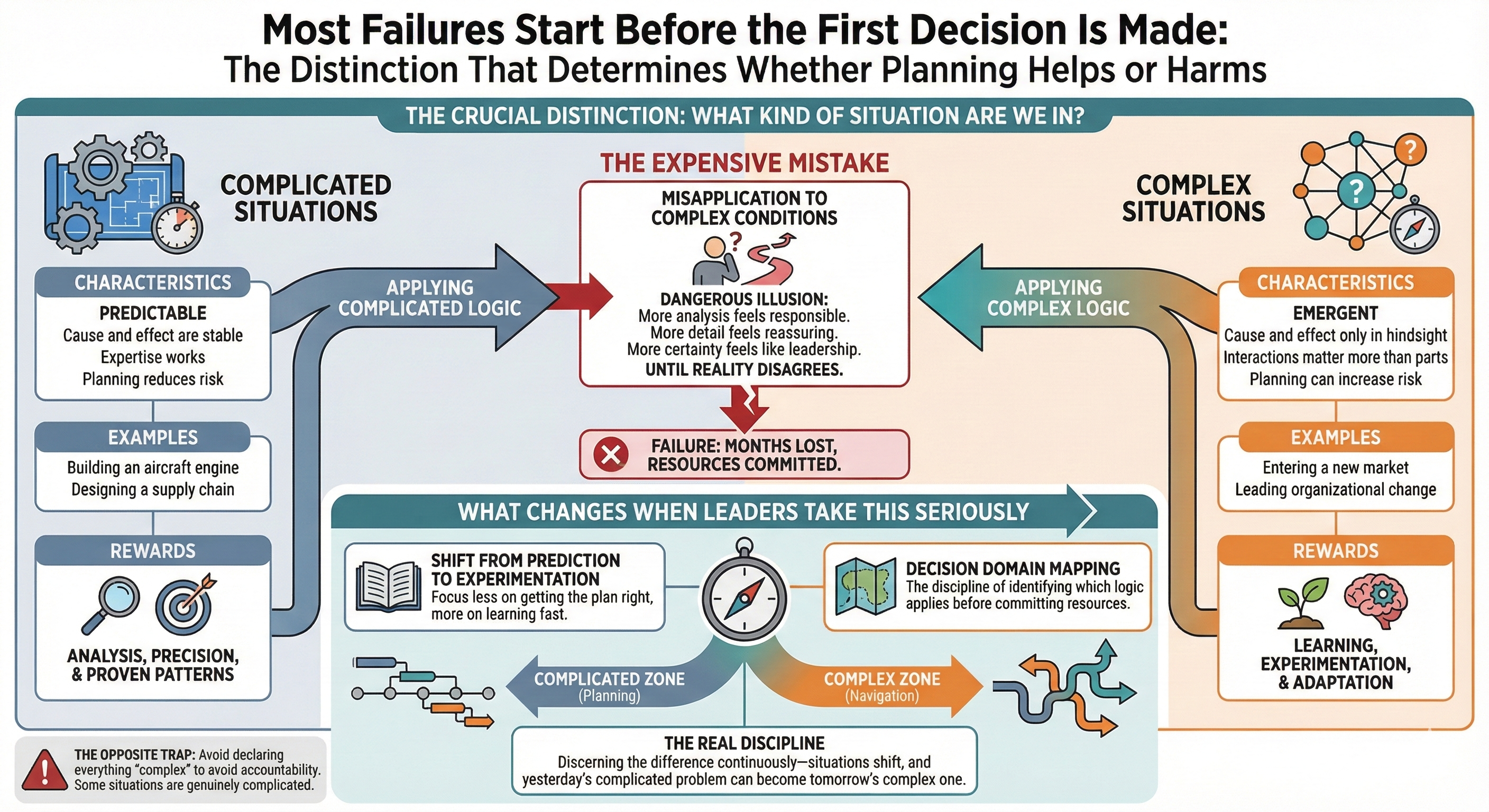

There is a crucial distinction most organizations blur: the difference between complicated and complex.

Complicated situations can be hard, but they are ultimately predictable. Cause and effect are stable. Expertise works. Planning reduces risk. Building an aircraft engine is complicated. Designing a supply chain is complicated. These domains reward analysis, precision, and proven patterns.

Complex situations behave differently. Cause and effect emerge only in hindsight. Interactions matter more than parts. Planning can actually increase risk. Entering a new market is complex. Leading organizational change is complex. These domains punish overconfidence and reward learning.

The Expensive Mistake

The mistake is not poor execution. The mistake is applying complicated logic to complex conditions.

This creates a dangerous illusion. More analysis feels responsible. More detail feels reassuring. More certainty feels like leadership. Until reality disagrees—and by then, months have passed and resources have been committed.

In Part 1, I introduced the Tautai Principle: the shift from planning to navigation, from prediction to sensing. This distinction between complicated and complex is where that shift becomes concrete. It determines whether planning helps or harms, whether expertise guides or misleads, whether control stabilizes or destabilizes.

Get it wrong, and every decision downstream suffers.

What Changes When Leaders Take This Seriously

Leaders who internalize this distinction stop demanding certainty where none exists. They shift from prediction to experimentation. They focus less on getting the plan right and more on learning fast.

Not because planning is bad. But because planning has a domain of validity—and recognizing that domain is the first act of navigation.

This is what I call Decision Domain Mapping: the discipline of identifying which logic applies before committing resources. It sounds simple. In practice, it requires leaders to resist organizational pressure toward false confidence.

The Opposite Trap

The common trap is declaring everything "complex" to avoid accountability. That's not leadership either.

Some situations genuinely are complicated. They reward careful planning and expert execution. Misclassifying them as complex leads to aimless experimentation when decisive action would serve better.

The real discipline lies in discerning the difference, again and again. Not once, but continuously—because situations shift, and yesterday's complicated problem can become tomorrow's complex one.

A Closing Question

Where are you still planning because it feels safer than admitting uncertainty?

This is Part 2 of a 12-part series introducing the ideas from my book, The Tautai Principle: Growing the Adaptive Organization (2025).

Next week in Part 3: Why yesterday's best practices become today's constraints—and when good management itself becomes the problem.

- How to work with Skills

- Your organization doesn’t need a better plan

- Most Failures Start Before the First Decision Is Made

- When Good Management Becomes the Problem

- Organizations Fail Cognitively Before They Fail Financially

- Crises Are Rarely Sudden

- Fast Organizations Can Still Be Too Slow

- Performance Can Look Great Right Before Failure

- Organizations Have an Anatomy We Rarely See

- Leadership Overload Is a Design Failure

- Innovation Fails Because of Structure, Not Ideas

- AI Won't Make Your Organization Smarter

- Adaptivity Is Not a Belief