Cybernetics and systems theory

Cybernetics is the (meta-) science of control and has been applied to many topics. A lot of the VSM vocabulary is best explained in its general version.

The universal machine

Cybernetics as a scientific discipline was born when a biologist and an engineer looked at the same diagram - one saw a device for character recognition, the other a human vision system. Norbert Wiener observed the exchange and understood that this was something big: a metascience of control and the concept of a cybernetic machine (biological, social, or technical) that has some way to stabilize its operation.

This generalization from mechanical machines comes at a price: cybernetic machines cannot be reduced, e.g. improved by improving one part - they can only be understood as awhole, holistically. They do not have a linear logic, feedback loops occur all over the place.

Cybernetics has developed into many application areas, from family therapy to automated weapon systems and---the focus of VSM---organizations.

The episode above explains why VSM uses the human nervous system and its differentiated functions as an analogy---like so many introductions into cybernetics.

Dealing with complexity

Classical management relies strongly on the machine metaphor for the organization and pursues its structured approach that emphasizes order, predictability, and efficiency. This view, deeply rooted in the early days of the Industrial Revolution, sees organizations as well-oiled, precise mechanisms based on well-defined processes and roles.

This approach comes to its limits with increasing complexity. The reduction into parts that can be optimized independently creates less valuable results. A better viewpoint must include the interdependency of the parts and the holistic view of a system. This perspective is often called the organism metaphor, which emphasizes the importance of adaptability, growth, and development. It stresses that organizations - like living beings - constantly interact with their environment and must adapt to change.

Dealing with complexity has its unique challenges, including:

- Measuring complexity: How complex is a system and its environment? We measure complexity as variety---what does variety mean exactly?

- Is the system adequately equipped to deal with the given environment? It needs to be well-equipped, i.e., to have the requisite variety to deal with the variety of things that come in through a channel.

- Alternatively, the incoming variety could be reduced through some filtering in the channel ("dampening the variety"). This is the opportunity to look a little deeper into the functioning of channels.

- Which tools does a system have to ensure its existence and viability? We will have to look into a system's stability, known as homeostasis, the types of stability, and their relation to viability.

Homeostasis and Dynamic Stability

Systems survive by using negative feedback loops to counter environmental influences and turbulences, i.e. if the direction deviates from the desired direction, the system counteracts it. We call this mechanism homeostasis.

Designing stability into systems is essential. The choice of stability analysis and control strategies depends on the specific characteristics and goals of the system being studied or engineered.

Stability does not necessarily mean a standstill. We distinguish between static and various degrees of dynamic stability, in which the system adapts to or even triggers environmental changes.

Oscillations

Fluctuations and instabilities in a system are called oscillations. A system is interested in limiting these oscillations before they produce negative effects.

In cybernetics, a damper for oscillations refers to an element or mechanism that reduces or prevents fluctuations or instabilities within a system.

An example:

Imagine a ship being steered by a helmsman.

- The helmsman constantly monitors the waves and wind and makes adjustments to the rudder to keep the ship on course.

- In this scenario, the helmsman acts as a damper for oscillations by minimizing the effects of external disturbances and maintaining the stability of the system.

Why oscillations are a problem

Oscillations in a system can lead to significant problems and affect the efficiency and stability of the system. In the context of organizations and companies, oscillations can have various negative effects.

- Waste of resources: Oscillations can lead to inefficient use of resources such as time, money and personnel. For example, if inventory levels constantly fluctuate between overstock and shortage due to fluctuations in demand, unnecessary inventory costs are incurred and production delays can occur. [1]

- Delayed decision making: Oscillations can cause delays in decision making because managers must constantly respond to new information and changes in the system. This can lead to a lack of clarity and direction and prevent the organization from achieving its strategic goals. [2, 3]

- Conflicts and tensions: Oscillations can lead to conflicts and tensions between different departments or teams within an organization, as each unit tries to protect its own interests and react to the fluctuations in the system. [1, 4]

- Loss of trust: Oscillations can lead to a loss of trust in the leadership and the organization as a whole. If employees feel that management is unable to control the situation, this can lead to demotivation and a decline in productivity. [3]

- Difficulties in planning: Oscillations make it difficult to predict future developments and create effective plans. This can lead to uncertainty and a lack of strategic direction. [5, 6]

We emphasize the importance of System 2 in the Viable System Model (VSM) to dampen these oscillations. System 2 acts as a kind of "regulator" that monitors the activities of the operational units (System 1) and intervenes to prevent excessive fluctuations. It is important to note that oscillations often arise from an imbalance in variety between different parts of the system. The sources also highlight the need to understand the underlying structures and processes that lead to oscillations in order to develop effective solutions.

Variety and Ashby's Law

Variety plays a vital role in cybernetics, both as a theoretical concept for understanding complexity, organization, and regulation in systems and as a valuable tool for conceptualizing systems. Variety refers to the number of possible states or outcomes a system can exhibit in response to different surprises: inputs, disturbances, or stimuli. The concept was codified by W. Ross Ashby, known as Ashby's Law. The higher this number, the larger must be the receiver's repertoire for reactions.

In cybernetics speak, the receiver's requisite variety, i.e., the set of its components and resources, must be large enough to handle the variety (absorb variety) coming in over the communication channel.

The greater the variety of a system, the more it can reduce the variety of its environment by control.\ --Ashby's law

When we dig deeper into the VSM, we will encounter cases where a system can reduce the variety but cannot absorb it all. In this case, a higher-level system must jump into the gap and come to help, i.e. absorb the residual variety.

For example, in a combined IT development with hardware and software components, problems may arise that cannot be solved by either the software team or the hardware team alone. A coordination system with other teams (VSM System 2) or the management of the whole development (VSM System 3) is needed to help out.

Channels and Regulating Variety

The communication paths between subsystems and the environment are called channels.

A channel refers to the transmission of information between systems or components.

A channel is always two-sided; think „feedback loop, "not „water pipe. "

Types of Channels

The term "channel" originates from communication theory and describes how information is transmitted from a sender to a receiver.

A channel can be physical or abstract and take different forms depending on the type of communication. In cybernetics, channels can be found in other contexts, such as:

- Human-machine communication: In this context, the channel represents how humans communicate with machines or computers. For example, a user interface consisting of a keyboard, a mouse, and a monitor is a channel through which users can interact with a computer.

- Machine-to-machine communication: In complex systems, machines or components can communicate with each other via specific channels to exchange information and work together.

- Organizational communication: In organizational cybernetics, channels can represent how information is transmitted from one part to another within an organization. This can include informal communication between employees or formal reporting channels in a hierarchy.

- Information processing: Channels can also be used in an abstract context to describe the flow of information or data between different system parts.

Channels are the physical connections or media through which information flows and how that information is encoded, transmitted, and interpreted. Cybernetics is concerned with analyzing and controlling communication processes and examines how information flows through channels in a system or between different systems to influence the system's behavior and performance.

Digging deeper into Channels

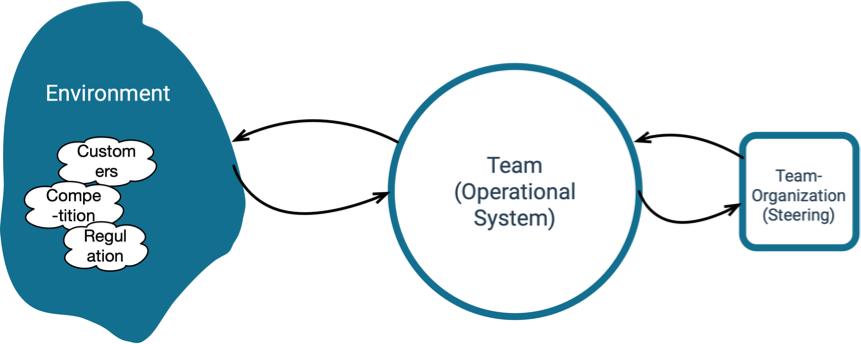

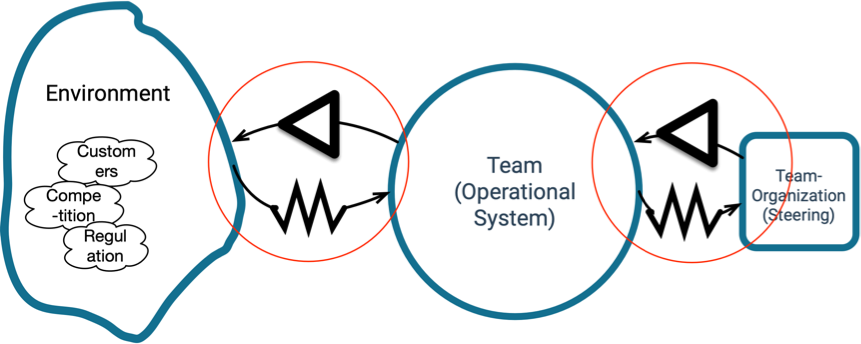

We started to visualize a team at the convention of VSM. The team is our operational system. The operational system is always represented in a triad, with its environment and (self-)organization.

The team, with its collective expertise and skills, is adept at handling requests from its customers and other sources. Its ability to manage diverse requests is a testament to its competence and adaptability.

As the team continues to succeed, it receives increasingly diverse requests. Despite this influx, the team remains resilient and adaptable. To prevent the team from being overwhelmed, we implement a filter into the communication channel, reducing the number of unwanted inputs. This successful management of increasing requests is a testament to the team's capabilities.

The next step would be to focus our message on customers by emphasizing our new reduced focus in our marketing brochures (amplify). This can make our product more attractive in the intended area and reduce unwanted feature requests.

This completes our look at channels. In general, a channel

- Is two-sided and build builds a feedback loop that is part of the control of the system

- Has a capacity

- Translates between the "languages" of the sender and the receiver

- Has an attenuator (think: filter) to dampen variety

- Has an amplifier to enhance the message to the receiver